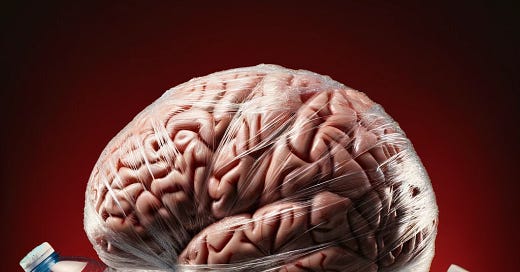

Note: This is the second story from my series of shorts inspired by toxins in our water. Read the first one here. After the story, I provided some links to news articles and studies about microplastics’ effects on brains. However, my stories are inspired by science, not necessarily based on science.

When Julie was still a 1-month-old fetus inside her mother's womb, thousands of microscopic plastic pellets infiltrated the amniotic fluid and crashed into the neural plate where her brain was beginning to form. After the plastic lodged inside the plate, they dissolved, emitting invisible traces of industrial chemicals into the glob that would become her brain.

As Julie continued to develop inside the womb, this process of microplastics crashing into her brain and dissolving into industrial chemicals continued every day, multiple times a day, throughout the gestation period. By the time she was born, Julie's brain had traces of more than one thousand chemicals, including, but not limited to: polychlorinated biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, bisphenol A, phthalates, organochlorine pesticides, butylated hydroxytoluene, heavy metals like lead, cadmium, and mercury, and much more.

Nobody - not her parents and certainly not her doctors - had any idea this happened. They definitely didn't think the expensive bottled water Julie's mother drank throughout pregnancy was corroding her brain, or that the expensive formula or the bottle she drank from or the diapers she wore or the wipes her mother used on her would continue the process of dumping toxins into her body, into her bloodstream, and into all her major organs.

As far as they knew, Julie was a healthy baby without any health problems. It never occurred to them that their child's brain had been rotting since before she was born.

As Julie grew up, her brain continued to get inundated by microplastics and chemical runoff. Everything she ingested and touched, from microplastic-filled water - bottled and tap - to food packaged in plastic to clothes made of plastic fibers to cosmetics filled with microplastics to air carrying microplastics it swept off from innumerable surfaces made of microplastics - plastics leaked chemicals into her brain that interfered with its natural chemistry. Plastics had not just become a part of her, but they determined who she was.

Her genetics had given her body a blueprint to develop a good memory and excellent critical thinking skills. But plastics destroyed that blueprint as the combination of toxins diminished her brain's ability to function, making her fickle-minded and reluctant to engage in complex thinking for extended periods. Environmental nurture conquered genetic nature. But she felt normal, and people considered her normal. And why shouldn't they? She was like everyone else.

Things changed when the headache started.

Her first week as a freshman at UCLA. Julie attended her first real college party - a big event at a fraternity house inside one of the many faux-Spanish colonial palaces in Westwood. Julie was tall and attractive with luxurious brown hair and an infectious smile, so she was used to turning a few heads when she walked into a room. But this time was different. Heads turned toward her, but as soon as the thumping bass from the Bad Bunny song hit her eardrum, everyone's face blurred into a confusing blob, and she felt a thunderous tunneling like a power drill digging into her brain.

The pain was fast and sudden - so much so that she didn't scream, she couldn't scream - she froze - the veil of shock on her face mirrored the shock inside. She tried to process what was happening, but had nothing to relate or compare it to. The strangeness of it all creating a confusion as visceral as the pain. The mob of blurred faces around her closed in on her, surrounding her, threatening to absorb and drown her as the drilling pain continued, digging deeper into her.

They're in on it, she thought. They're doing this to me.

She imagined the blurry blog surrounding her as drill-wielding demons, knowing this was crazy and couldn't be true but also thinking it was real and completely true. Without saying a word to her friends, she ran out of the house, almost tripping on the front steps, and vomited violently on the sidewalk. She hadn't drunk any alcohol or taken any drugs, but to anybody watching, it looked like she had taken anything and everything. The social shame and the intense pain wrestled with each other, and she didn't know which was worse. All she knew was that something was wrong, and she didn't know what.

The next day, the pain was different. Instead of a drilling feeling, she felt angry incisions slicing into a precise corner of her brain. Julie could feel the exact point where the pain originated, and she imagined a woman in red heels stepping onto the rear right edge of her brain, digging in like she was stubbing out a cigarette. A rude, deliberate pain made her feel degraded and discarded. It made her wonder if somebody had poisoned her. Maybe her roommate poisoned her. The roommate, Dana, was a biochemistry major and a dedicated student. Although just a freshman like Julie, she knew she wanted to work in research and was already working on getting into a PhD program. Underneath the torrential pain inside her skull, Julie was sure Dana did something.

When Dana opened the door to the dorm room, it was late, and the room was dark. But Julie was sitting on her bed, waiting. She watched Dana walk in, put her backpack down, and flip the light switch. That's when Julie jumped on her from behind, knocking her down, and squeezed Dana's neck from behind with her forearm.

"What the fuck did you do to me?" she said. "What did you poison me with?"

Dana grabbed onto Julie's hair and pulled with all her strength. To Julie, it felt like hot razors searing her scalp and scalding her brain. She let go of Dana's neck and cried as she begged Dana to let go of her. Dana let go and ran out of the room. Julie ran to her car to get out of there before any police arrived and drove herself to the hospital.

On the way, the pain alternated between drilling and slicing. For brief moments, it would go away completely. But the memory of it stayed, and even though it was gone at the moment, she knew it would be back, like an unwanted and unbearable visitor who would return any time they wanted, and you had no say over it. And it would come back, always harder than the last time, like it was making up for lost time.

Waiting in the emergency room, the incessant lights and constant noise were like dump trucks unloading massive piles of pain into Julie's brain. She tried to sit and wait, trying not to be a burden, worried that somebody might think of her as pushy or privileged, but after 30 minutes, her facade collapsed, and she screamed louder than she ever thought she could: MAKE IT STOP!"

But they couldn't make it stop. After nurses pushed her to the front of the line, the ER doctor, a stout, short-of-breath man in a surgical mask, looked at her vitals and shrugged.

"I can give you something for the headache, but you need to see a neurologist," he said. "The front desk can help you make an appointment."

The front desk helped with the appointment but could do nothing about the thousands of people in the Los Angeles area with Cigna insurance who needed to see a neurologist ASAP. The next appointment wasn't available for three more months.

"I could be dead by then!" Julie told the woman with thick eyeglasses and a purple stud nose ring. "What if it's a tumor? What if I have brain cancer?"

The woman rolled her eyes.

"If it was that serious, I'm sure your doctor would have done something," she said. "Do you want the appointment or not?"

Julie confirmed that she wanted the appointment and apologized for her behavior. The woman shrugged and called for the next person in line.

Sitting in her car, Julie squeezed the steering wheel with both hands. She squeezed until her hands were numb, gnashing her teeth, deep breaths, and long exhales, trying to wring the wrathful pain out of her supplicant body. Three months just to know what was happening. And then, who knew how long until it was fixed? It seemed like a deranged joke, an unbelievable story that shouldn't be told. She looked at her hands and saw them turning pale, bloodless white. But she wasn't sure if that was really happening. She wasn't sure about anything other than that she didn't want to be inside her head anymore.

As she focused on her skinny fingers, the lines on her knuckles, the tiny hairs poking out from them, she wondered if they weren't really there, if she wasn't in this car, if she wasn't really here.

And then the pain went away - lifted off of her like all those days of excruciating, unbearable pain was nothing but a thin sheet that could be swept away with a light breeze.

Julie smiled - a grateful and knowing smile - grateful for the knowledge that what she had to do now was live like nothing was real or the pain would return.

She turned her car on, drove into the street, got on the freeway, and slammed the gas pedal as she drove into the opposite lane. The powerfully deafening crashing sound of a 26,000-ton cargo truck smashing into her 3,000-ton Hyundai Sonata at 60 miles per hour was the most beautiful sound she had ever heard because it was the sound that meant her pain wouldn't come back.

As Julie's broken skull leaked the remnants of her brain onto the pavement, billions of half-dissolved microplastics swirled in the goop and reflected the cargo truck's headlights, creating an eerie glitter like stars in a blood-red sky.

To learn more about the effect of microplastics on the brain:

This is beautiful and gnarly at the same time. I read about microplastics in breast milk a while back and it stuck with me. This was a great exploration of that.

Awesome!