For Garret, being able to go outside for a walk felt like somebody was playing a trick on him.

It felt strange to believe he was really allowed to do it - like if he did, a bunch of cops would jump out of the bushes, tackle his ass to the pavement, and put him right back in prison. You really thought we were gonna let you out, sucker?

Laughing at him as they threw him in the back of a van with no seats, him rattling around like an empty coke can on the long drive back to Ocala, a city he lived in for 12 years but never walked its streets.

He knew this paranoia was just the crazy, institutionalized part of his mind acting up. People say old habits die hard, but they don’t die - they stay alive and well, always ready to spring out of nowhere like those imaginary cops and fuck with you when you least want them to. Whenever Garret stepped outside, he tried to focus on the fresh air and the sunlight and the fact that he was not in prison anymore. But the possibility that he could go back punked him so bad, all he wanted to do was stay inside his room, which is exactly what he did ever since he got to the halfway house a week ago.

Him staying inside all the time looked weird and he knew it. He knew he had to get over it, too. In a few days, he’d have to visit his parole officer . And if the PO found out he hadn’t been applying to any jobs and barely left the house, it wouldn’t be good. But Garret stayed put and read the Bible or watched Judge Judy if it was on. The problem at this very moment, however, was that he needed cigarettes, and there was nobody around at the moment to go pick him up a pack. Everybody was at their job or looking for one. It was just him and the cranky sonofabitch who looked after the place during the day. And that guy sure as hell wouldn’t walk down to the quickie mart for him.

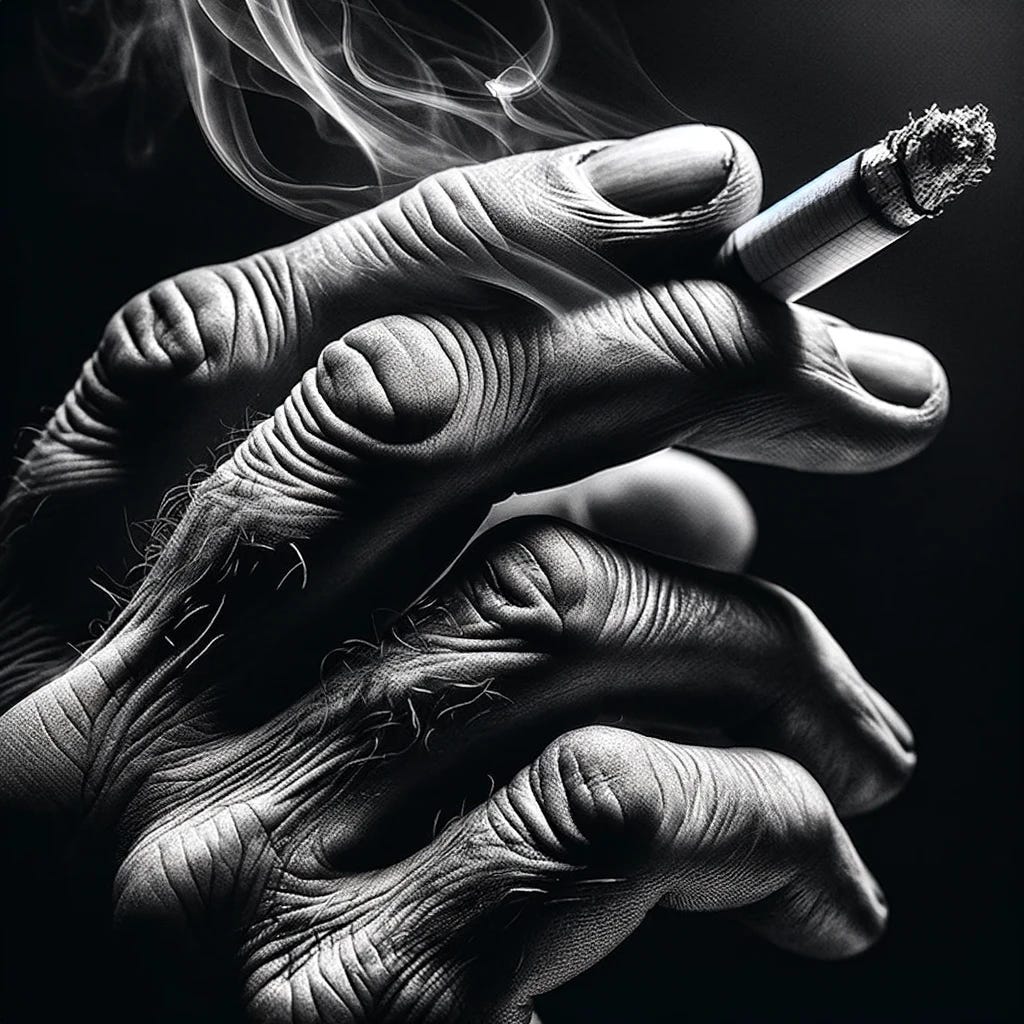

Garret considered waiting it out. Wait until Marcus got back. Marcus always willing to take that stroll if you give him a couple smokes. But Marcus wouldn’t be back for hours and Garret was down so bad for a nicotine fix, he could almost taste the stale smoke scorch the inside of his throat. So he put on his shoes and headed out.

Everything’s fine, you dumb motherfucker. Just walk down the street is all you gotta do.

Garret stepped outside and closed the front door. He had to give the door a hard tug to get it shut, rattling the windows hard. He imagined the windows shattering and him getting blamed for it and violating his parole on some property damage charge. He looked closely at the windows. They were fine. He wished they’d fix that damn door.

Garret walked down the sidewalk with his head down and hands in pockets, wanting to appear as non-threatening as possible.

He entered the quickie mart and went to the cold section where the beer was. He wasn’t allowed to have any alcohol inside the halfway house and drinking was a violation of his parole, but he liked to look, see what they had. He wanted a drink, wouldn’t mind one at all, but he was afraid of how he might react. A part of him was glad he wasn’t allowed to drink. Otherwise, he might take a taste and get in that crazy mind state again. The last time he partook, he got the bright idea to hold up a quickie mart just like this.

Cheap whiskey on his breath and crack smoke in his lungs, he pointed a gun at the cashier and told him to empty the register. There was only 48 dollars and change in it, and Garret knew he fucked up - not even enough for an eighth. Maybe a couple rocks, but he needed more than that. He took the money anyway and a few packs of Marlboro Reds, too. He said “thank you” to the cashier as he took them.

And when he turned his back to leave, the cashier took out a gun and shot him in the ass. Garret fell forward and accidentally fired his gun. The bullet went through the window and into the tire of his car. Before he realized what happened, the cashier jumped over the counter and whacked him in the head with something big enough to knock him out.

When he woke up, he was handcuffed in a hospital bed, two mean-looking cops sitting at his bedside.

“Rise and shine, dumbass,” one of the cops said. “Now why in the hell did you shoot your own getaway car?”

The cops laughed heartily. Garret’s head and ass hurt immensely. Hurt so bad, he couldn’t even be mad at these cops laughing at him. But he knew he fucked up big time and would be going away for a while. If only he didn’t pick up that bottle.

Staring at a 6-pack of Modelo, he wondered if, after 12 years of no boozing and almost total sobriety (he took a few painkillers while locked up, but that was about it), if he’d still have that crazy erupt inside him after taking a drink. Or did prison beat it out of him? There was only one way to find out, but he wouldn’t find out today. He only had enough money for cigarettes. He closed the refrigerator door and went to the counter.

The lady at the cash register was in her 50s, tired face and tatted arms. She looked like she may have done a little time herself. She took down two packs of Marlboro Reds from the holding place above and took Garret’s twenty dollar bill. Cigarettes were so expensive now, he only got a dollar and some change back. Not enough for anything else. He’d need to get a job very soon. Maybe one at a quickie mart if they don’t look at his record. He said thank you and left.

Outside, Garret ripped the cellophane of his Marlboros and put a cigarette in his mouth. He lit up and took a deep drag, savoring the toxins inside him. It was a pleasant Miami in February day: 77 degrees and sunny, the kind of sunniness that sparkles and makes everything seem like it’s brand-new. Garret grew up around here and the brightness was something familiar, deeply ingrained into his memory. Up in Ocala, the sunlight was different. Less shine and glimmer. Dull. Garret noticed it during his first few months up there, but he had to forget it. He had to train himself to not think about those things he couldn’t do anything about. But now, he was able to see again how the South Florida sun puts a shine on everything, and he wondered how often his daughter got to enjoy it. He imagined her smiling as the sun graced her face and the thought made him smile, too.

She was only six months old when he went in and that was the last time he saw her. He couldn’t blame his baby mama too much for leaving. He hadn’t done shit for her. But for the first couple years, it bothered him pretty bad. He tried to rationalize it. He’d tell himself that the girl was better off without him, and so if he was a part of her life, he would just be holding her back - she’d be one of them kids with a dad in prison. He knew what that was like and he didn’t want her to be like him. He knew it would always give her an excuse to do something stupid.

- Why’d you do what you did?

- My daddy’s in prison. My life is hard. This is what people do.

On the other hand, he was her father and he thought he should be involved in some way. But after about two years in Ocala, Garret decided to put all that out of his mind. Let go and let God, the best philosophy he ever heard.

First time he heard someone say it, he knew right away it stopped a lot of people from killing themselves. When you want to end it, the only way to stop that shit is to understand that you can choose to continue without that crushing pressure. It’s just a little thing, but it can be done.

Let go and let God.

Garret had to. That was his only choice. Let go and let things happen as they may.

He crossed the street, looking both ways - no cars were coming, but looking for them reminded him that his daughter died in a car accident three years ago when she was nine-years-old. He didn’t hear about it until almost a year after it happened. When he did hear about it, he wanted to cry, but couldn’t. He didn’t know the girl. He had no idea what she looked like, what she was like, the things she liked to do. And now she was dead. He realized that she didn’t know anything about him, either. That’s when he cried, but he felt ashamed because he wasn’t crying for her. He was crying for himself. Her name was Julie. That’s the only thing he knew about her.

The baby mama was driving. She survived, but was hurt pretty bad. That’s all he knew about the whole thing. He wished she had died, too, not because he hated her - he didn’t - but so that Julie wouldn’t be alone. He knew that’s not how things work, but it made sense to him. He couldn’t help but imagine Julie somewhere scary and all alone.

He exhaled and watched the smoke float up and disappear. It reminded him of his life - just a cloud of smoke vanishing and leaving nothing behind. Forty-two years with nothing to show for it but a rap sheet and a dead daughter he never knew.

He headed towards the halfway house, and halfway there, he realized he wasn’t looking over his shoulder for the cops, afraid they’d jump out of the bushes and bust him.

In fact, there wasn’t a goddamn thing in the world he cared about and nothing in the world cared about him. It was a cold realization, but strangely comforting - like you’ve been told an ugly truth, but appreciate that you know anyway.

He made a left where he was supposed to make a right and headed toward a liquor store a few blocks away. He was about to find out if that crazy was still in him. Maybe Julie wouldn’t be alone for much longer.

Let go and let God.

Got transfixed by this one. "Her name was Julie. That’s the only thing he knew about her" hit so hard.

Just great, Ray. I like that you're insisting on getting those shades, hues and muted and profound colors in. A richness. Keep pushing it.